The language wars

In February 2011, a revised edition of the Romanian Thesaurus will roll off the presses, after the Academy’s linguists have amended the definitions of the words „kike” and „gypsy” in response to pressure from civil society.

Late this summer, the word kike caused a linguistic and political storm, after an NGO accused the Romanian Academy’s Linguistics Institute of anti-Semitic sentiment. The Institute received a letter from the Center for Combating and Monitoring Anti-Semitism, which asked that the word’s definition be changed. The dictionary’s most recent edition, published in 2009, featured kike as a familiar word, although the dictionary’s 1998 edition had explained it as slang and a pejorative. For Marco Maximilian Katz, the Center’s president, the word “expressed hatred in its most primitive form against people who happen to have been born Jewish.” He demanded that the linguists also introduce anti-Semitic in the new definition.

Katz, who is fifty years old and runs a Bucharest hotel, was inspired by a similar appeal filed in February 2011 by several Roma rights organizations that had demanded the amendment of one of the definitions of the word gypsy: “an epithet assigned to a person of bad habits.”

The Romanian Academy’s Linguistics Institute is a state-run institution in charge of regulating language – the dictionaries they publish are official guides that school textbooks, books, official documents and mass media language observe.

Having entered the Romanian language via Old Slavic before the late 19th century, the word kike (jidan) was used almost exclusively by popular media at the time, to which the word Jew was virtually unknown. During the interwar era, it was taken over by the far right, which had a very strong press behind it. “They created an over-saturation. It became toxic; it is a toxic word, you can’t dub it familiar now,” says anthropologist Andrei Oişteanu. Kike would frequently show up in the speeches of inter war ultra-nationalists and was solidified as a slur when Romanian ruler Marshall Ion Antonescu initiated an ethnic cleansing against the Jewish population.

Roughly 8,000 Jews live in Romania today, whereas the Romania of 1940was home to the third largest Jewish community in Europe and the fourth largest worldwide, after the USSR, Poland and the United States. (During the Holocaust, between 280,000 and 380,000 Romanian and Ukrainian Jews died or were killed in Romania and the territories under its administration.)

Out of the 27 European Union member states, Romania ranks 20th in terms of tolerance toward Jews and 12th in terms of tolerance toward the Roma, its second largest ethnic minority after Hungarians. With respect to Roma intolerance, Romanians find themselves in line with other European Union citizens. However, when it comes to intolerance against Jewish people, it can be said that Romania is among the most anti-Semitic countries in the European Union, as indicated by a report from Soros Foundation Romania.

Following the appeal issued by Katz’s NGO, the Romanian Academy’s Linguistics Institute acknowledged the familiar label as a mistake and, several weeks after the appeal, promised that the forthcoming 2014 edition of the Romanian Thesaurus will label kike as pejorative, not recommended term.

A month after that declaration, in late September, the Institute announced it would go a step further and immediately publish a new edition of the Thesaurus with amended definitions of the words kike, as well as gypsy. This came in response to the threats of Roma activists to launch a discrimination suit against the Institute if the word gypsy was not amended in a timely fashion.

The linguistic debates between Jewish and Roma representatives and the Academy’s linguists lasted for over a month. In the end, Kike was not termed anti-Semitic, but the new definition will stipulate that the noun “is employed as an expletive, racist term, as well as with the neutral meaning of Jew in outdated, popular language,” according to Monica Busuioc, chief of the Institute’s Lexicography Department. The word gypsy received the often pejorative label, and the “epithet assigned to a person of bad habits” was changed into “expletive epithet assigned to a person of rude behavior.”

It’s hard to believe that, once published in dictionaries, the words’ new nuances will produce a more tolerant society overnight. According to the Council against Discrimination, the word gypsy has been increasingly used by the press during the past three years. However, the Council does see progress.

“Dictionary definition amendments cannot change the collective mind-frame, but they can regulate an issue that is not just linguistic, but also social and legal,” Oişteanu says. “In a hate speech case, if the judge sees the dictionary has kike pegged as a familiar word, they’ll say no harassment was committed. This debate showed society is alive; if it hadn’t responded, it would’ve meant it was dead.”

Acest articol apare și în:

S-ar putea să-ți mai placă:

Iarna vrajbei noastre

Vom reuși să trăim împreună într-o țară împărțită în două?

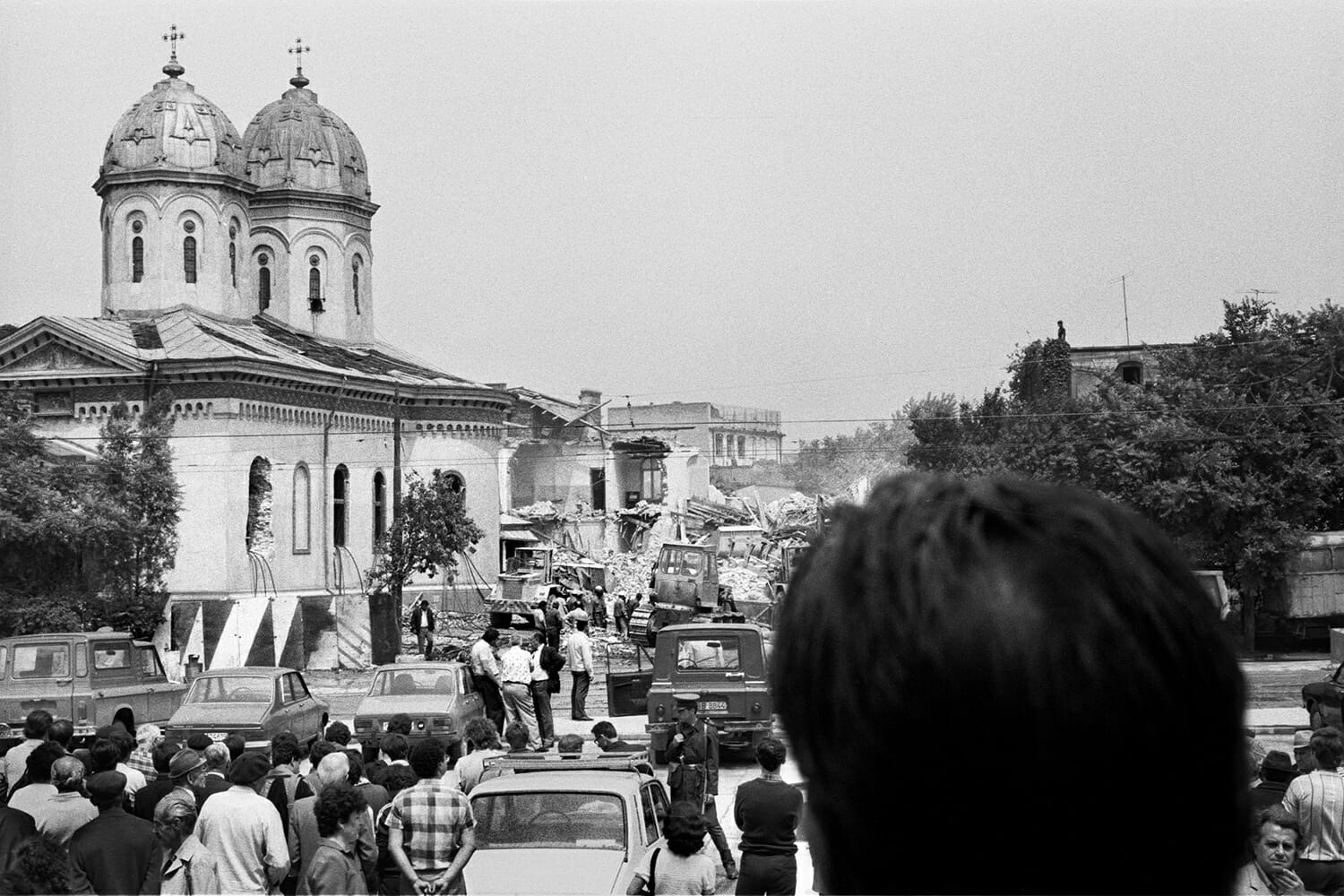

Orașul întrerupt

Un irlandez descoperă, în București, cât de puţin știm despre locurile în care trăim.

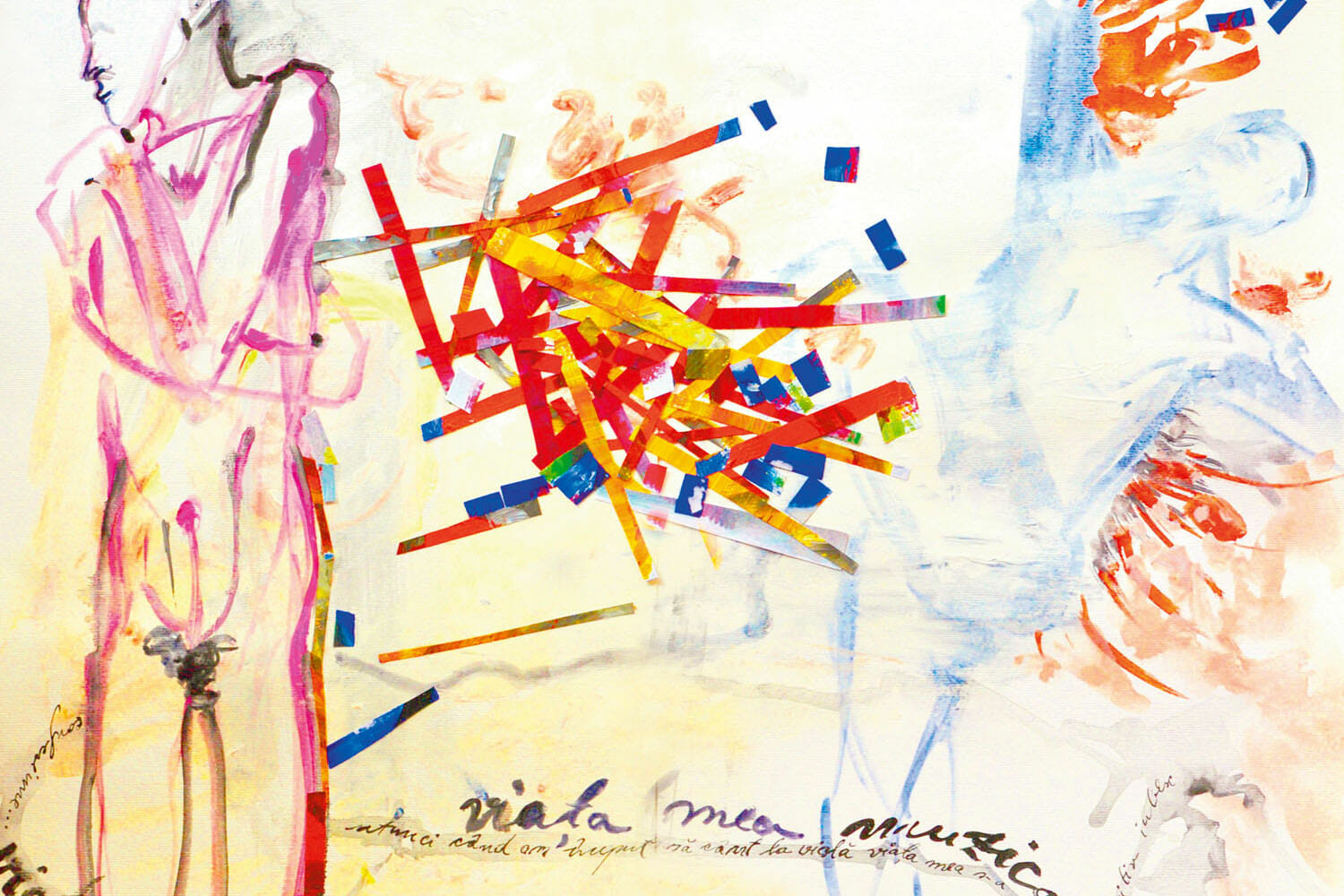

Notă cu notă

În 30 de ani de muzică clasică am învăţat că nu poţi cânta bine la un instrument fără să iubeşti detaliile.