Ordinary

The peace of being yourself somewhere far away or the familiar chaos of being at home. Which would you choose?

Note: This is the English translation of an as-told-to story originally published in issue #34 of DoR magazine. You can read the Romanian version here.

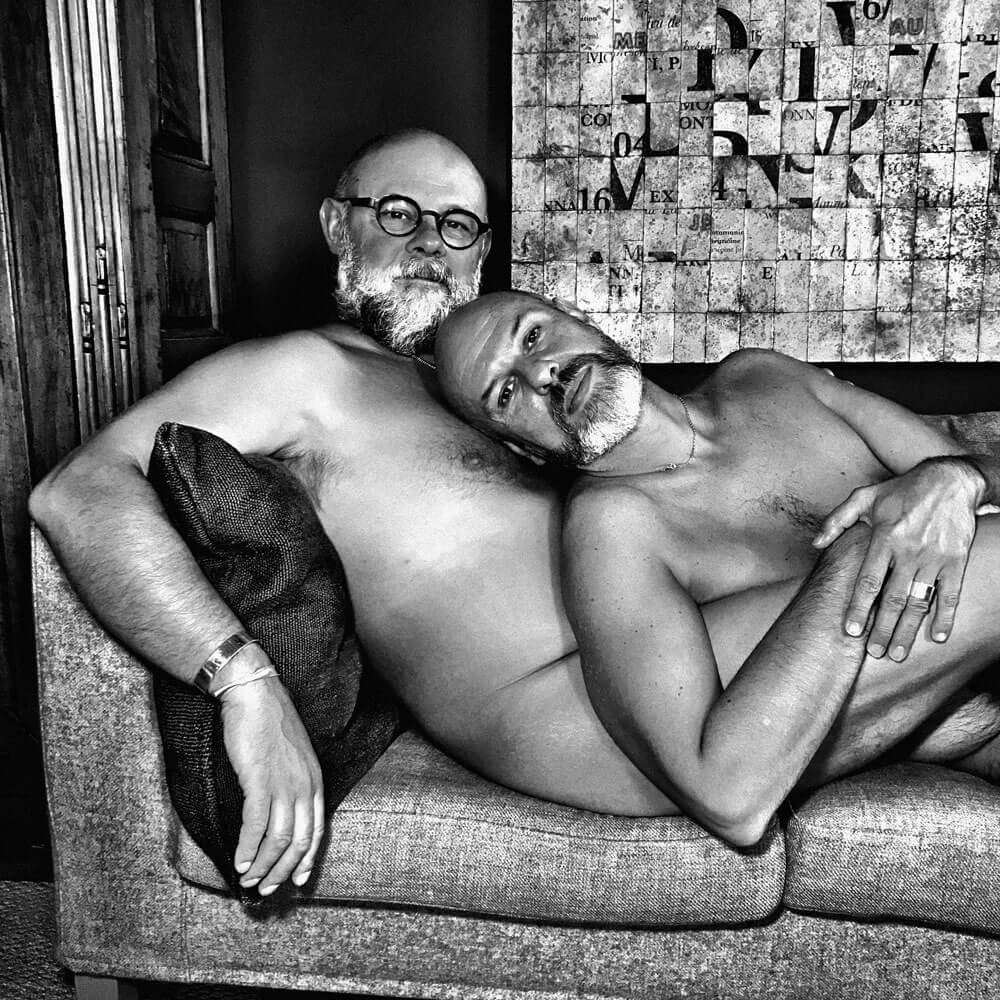

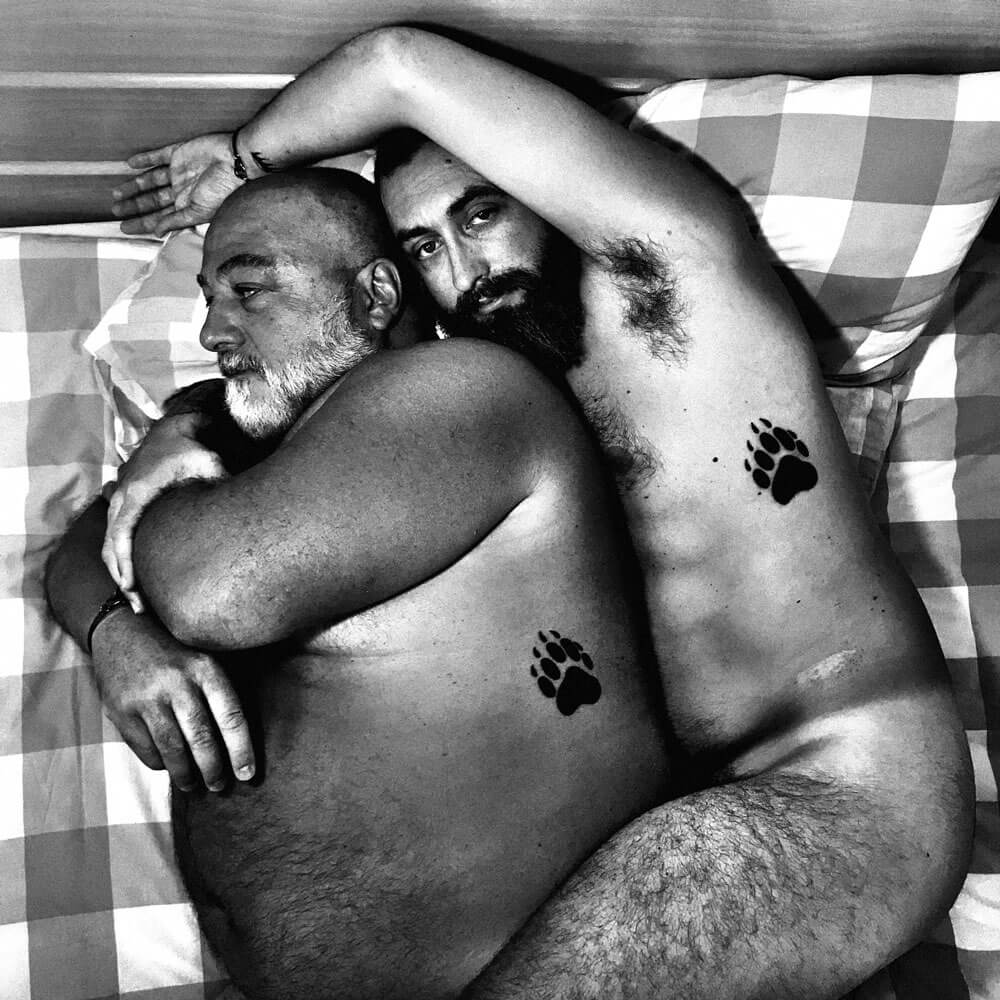

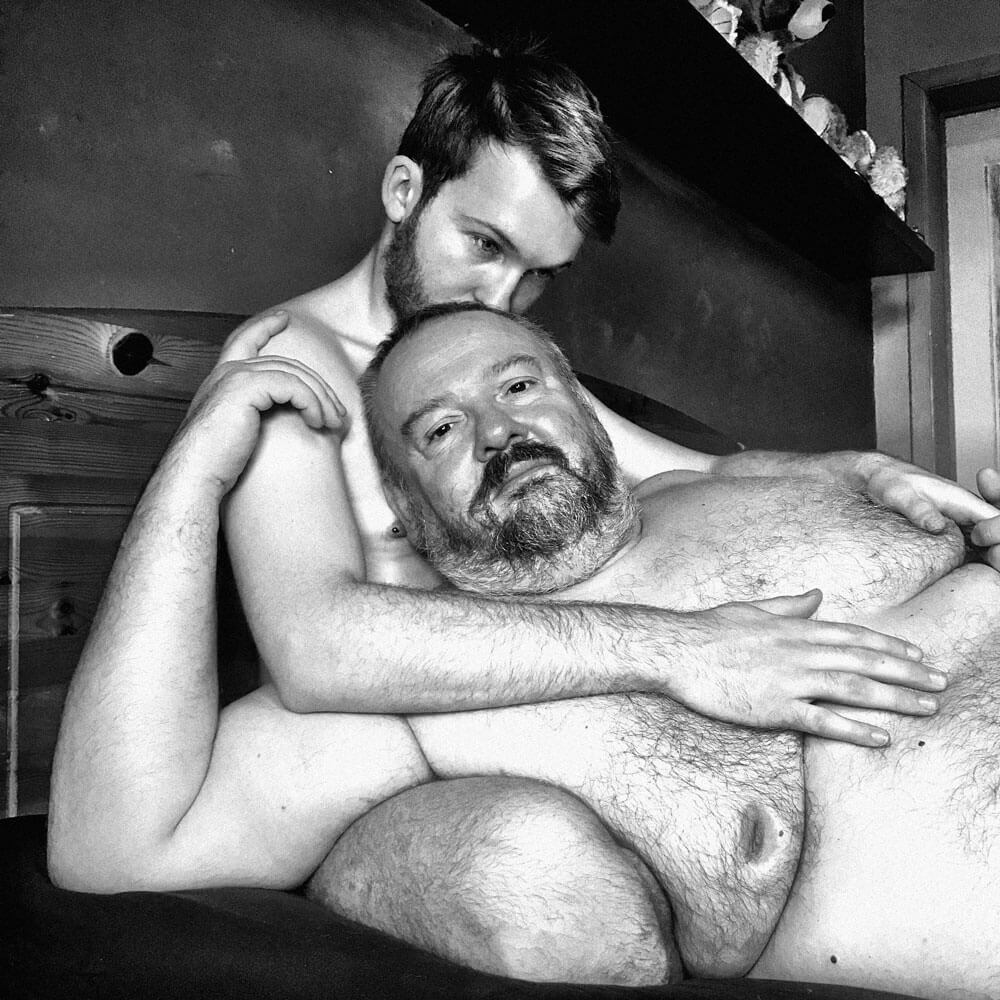

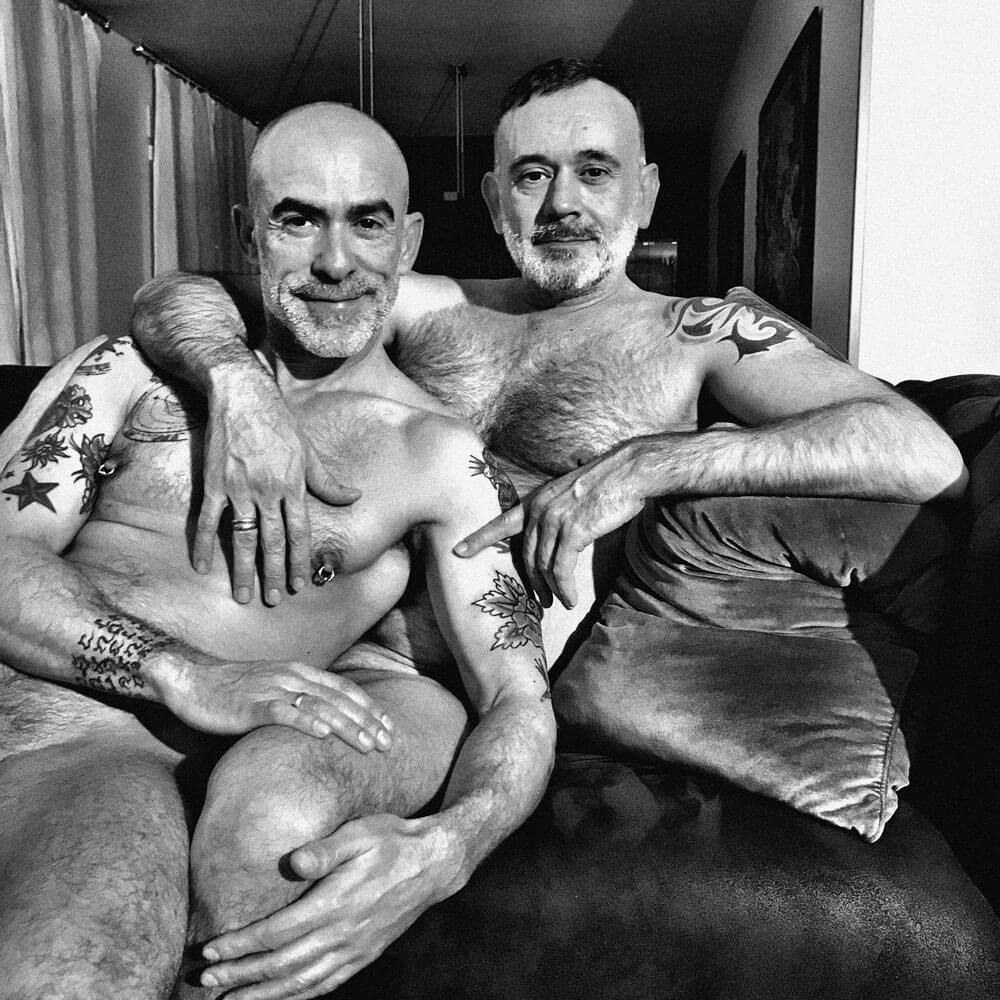

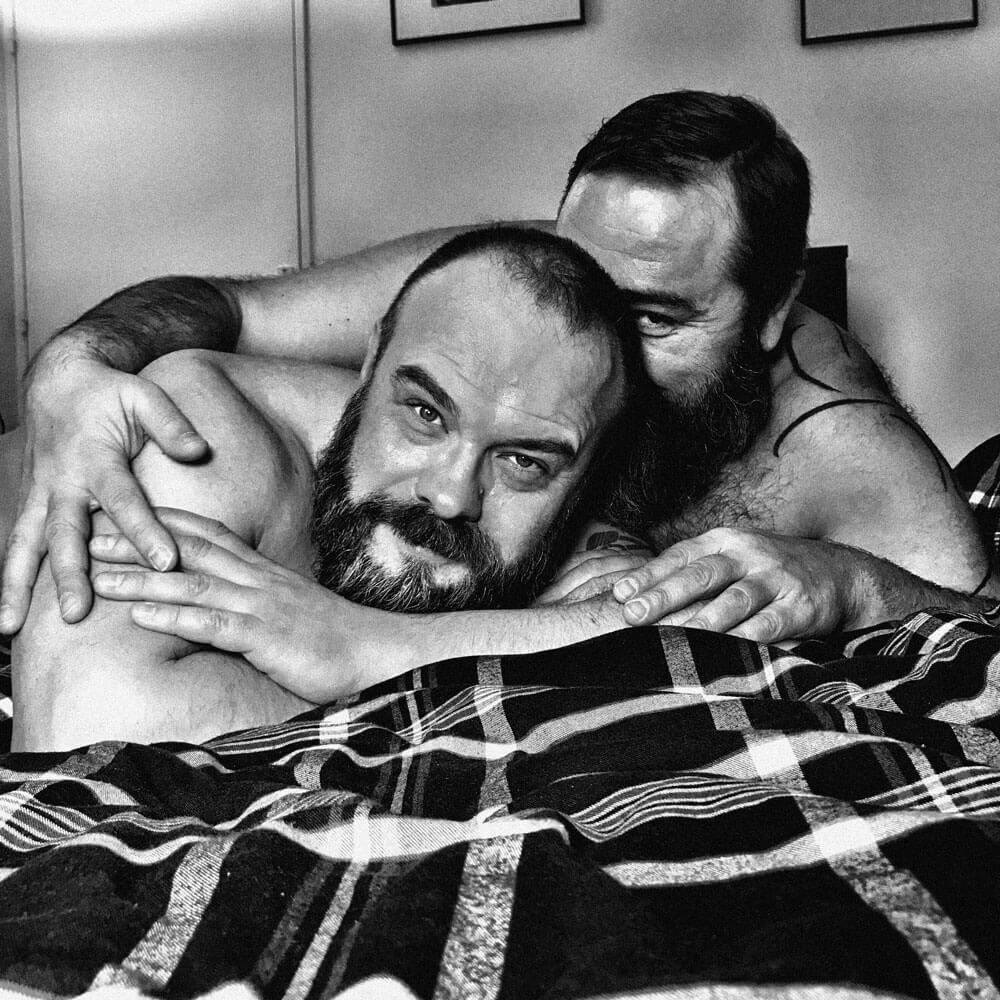

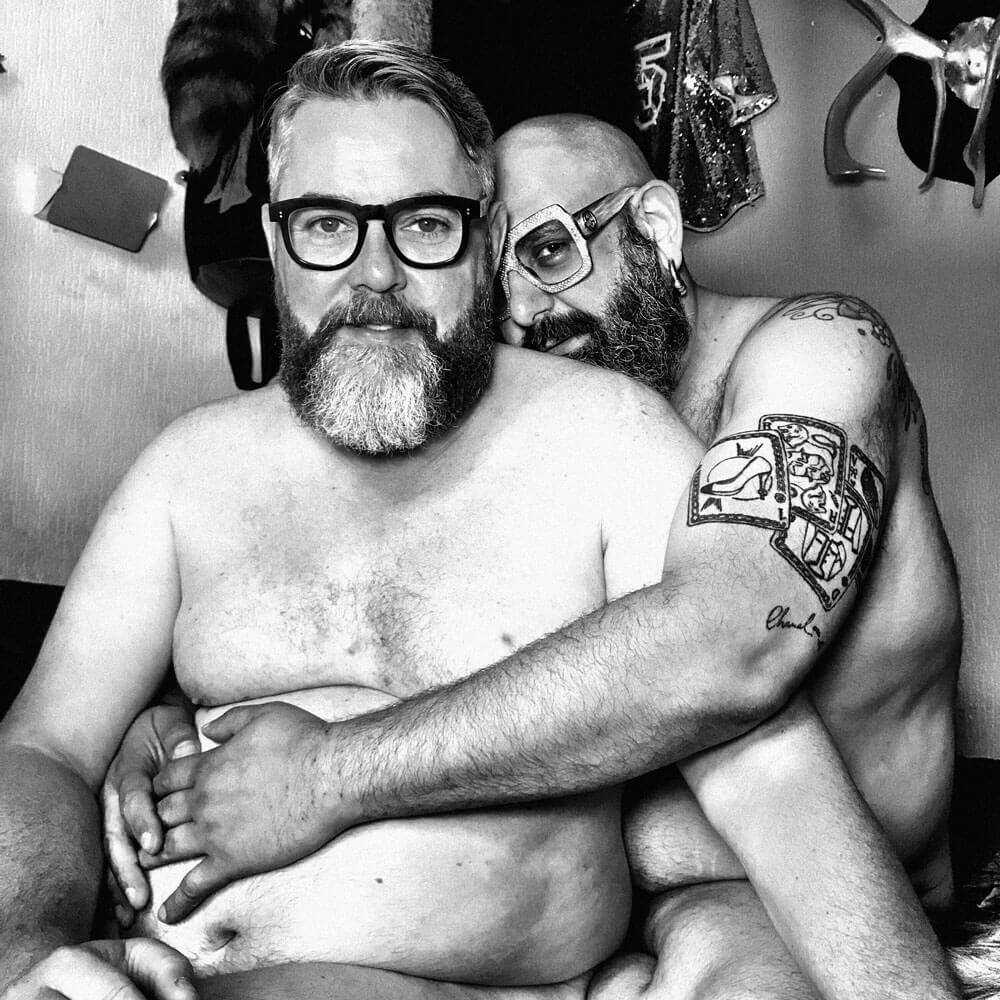

Tiberiu Căpudean is an activist and a communications professional, he is 44 years-old and has lived in Romania since birth. His projects, NAKED and FAMILY, in which he photographs gay and bisexual men (of different ages and nationalities, single men and couples) in the intimacy of their own homes, have been exhibited in Bucharest, Brussels, Paris and Madrid. In November 2018, KulturForum Europa in Cologne awarded Tiberiu with The European Tolerance Award, a distinction that for the last 25 years has been given to people and institutions who have contributed to the development of human rights. He never thought he would reach such heights: after college Tiberiu worked in advertising and publishing, he worked for the British Embassy in Bucharest, and volunteered for The Romanian Association Against AIDS and for other NGOs where he took care and raised funds for abandoned children and for children and adults living with HIV or cancer; as well as for the LGBTQ community as a member of the board of directors of ACCEPT. A close relationship with his mother has both defined his life and made him reevaluate it after her death. This year, Tiberiu decided to move to Madrid, driven out, he says, by the lack of respect towards the dignity and validity of some intimate experiences – of love and of suffering – and by the lack of hope that he can have a good life here.

In greater depth below is the story of these events and decisions, as told to us by Tiberiu. The interview was edited for clarity and conciseness. The accompanying images are part of the FAMILY project, more of which can be seen on his website.

I was an only child, and I had a very close relationship with my mother. We felt that closeness without having to ever try. I think the advantage was that she had me at 23, and had probably not forgotten what it was like to be a kid. She spent a lot of time with me, even though she worked just as much as my father. She worked as a chemical-pharmaceutical researcher but, despite her job, she was an extremely creative person. She used to do a whole load of fun stuff; she’d come down to my level as a kid, and never seemed at all preoccupied with what people might say.

My parents had very different natures. Mum was always an extrovert, and my father an introvert. She’d tell me that the most important thing was to be myself, even if that meant not conforming to the norms, whilst it really put my father out during my teens that I was wearing my hair long and ripping my jeans. I think he would have preferred that I kept a low profile. While there was a father figure around, he wasn’t very involved.

When my mother said she was worried the kids in school would make fun of me if she’d divorce my father, I told her that I couldn’t care less; she had to do what she felt. And “we got a divorce”. I was seventeen. Quickly, the atmosphere at home changed. It was quiet.

I know that I was attracted to boys since very young, from five years-old. For as long as I remember, I was checking out boys, not girls. But growing up in a society where you heard “cocksuckers”, “faggots”, “freaks”, from a very young age I realised I was doing something wrong, that I was guilty of something, and that no one could possibly know about it. That was why I initially had girlfriends and so on. I thought my mum knew I was gay, but she did not.

The first time I kissed a man was when I was thirty-one. I was in Paris. I just summoned up all the courage I could and entered the first gay bar I saw. I saw that it was something completely normal; there were men who looked like me: shaved heads, beards, dressed in jeans, T-shirts and boots. They had ordinary jobs: some were engineers; others accountants, doctors, truck-drivers. It was then that I kissed a man for the first time, and it was terrific.

I met Andrew a year later. He was working at the British Embassy in Bucharest; he had come to coordinate an EU-financed anti-corruption project relating to the Romanian Customs Authority, and I was working in advertising. It was kind of hard for us to see each other because both of us worked and traveled a lot. Finally, we met up for dinner, and it was really natural. He was a really warm guy, very clever, and had a very particular sense of humour – I think this was what really won me over. Pretty soon, he moved in with me and never left.

I came out to my mother when I was thirty-two. She came to my place, we were eating ice-cream with a spoon straight out of the bucket. I remember she said: “Look, I know it’s none of my business, but I want to ask you if you’re single because it’s hard for you to find someone who meets your expectations or if you just prefer to live like this, without ties to someone”. In all recent years, I hadn’t had a girlfriend and I was going on holidays either with friends, or on my own. I told her that I was actually in a relationship and that we were living together. That left her speechless for a moment. She looked around and saw there was nobody else. “How do you live together?” she asked. I told her: “It’s Andrew.”

She knew Andrew from my circle of friends who would come over to her place at Christmas. Her house was full of my friends: both boys and girls, gay and straight. Mum loved them all. She knitted them socks with their names on them, made them their favourite cakes, wrote them cards on their birthdays. My friends would go to her place without me and talk about things that they couldn’t with their own mothers.

So then she said, “OK.” I thought she didn’t get it. Not a muscle on her face moved. “Andrew is my partner,” I felt I had to repeat it. And she replied: “I understand. Are you happy?” I said I was. “For me that’s the only thing that matters.”

Andrew and I have been together for thirteen years now. We signed our civil partnership in the British Embassy in 2011, the day my mum turned sixty. I hate saying that we are in a civil partnership, I never say “he is my partner”; I say “he is my husband.” He has proven to be the right person, and we’ve lived through some really hard times together.

Mum’s illness happened really quickly. We were at home, after a trip away for her birthday, and she developed a fever. She hadn’t had a head cold in twenty years. She tried to fix herself up with tablets and vitamins but after a week of having a high temperature she realised that it was something other than an ordinary cold as her fever was regularly peaking and causing her to lose consciousness.

She was admitted to the hospital. After two weeks the medics called for a panel review because no one understood what she had; her tests were clear. They sent her to another doctor in another hospital, and after another two weeks of keeping her under observation, she was diagnosed.

I found out first. Mum was in the ward and I was in the doctor’s office. The doctor said: “I’m very sorry, she has cancer. It’s in the T4 phase. It has spread to her liver.” Then, it went quiet. I had never experienced a moment like that, and haven’t ever since. Everything just stopped. After the word “cancer”, I heard nothing. He spoke some more, showed me some papers. I understood nothing. My grandmother had died of cancer; all I was thinking was what do I do now. How do I fix this, what do I tell her, when do I tell her, how do I tell her.

I was the one that told her. She was very calm about it, didn’t freak out at all. She said: “Ok, cancer. What can be done? What are the options?”. Mum was used to dealing with hospitals because she had been diagnosed with lupus. She had lived with it for thirty-three years until it became undetectable; it was something extremely rare. Then in ‘97, she had ovarian cancer, which was dealt with well, total hysterectomy, she recovered really quickly and could see a life ahead for herself. She wasn’t the kind to be knocked down easily. After the diagnosis, she was admitted and performed surgery on twice over the course of a week, and each time she contracted a bacterial infection.

I saw this in the tests, because she was being tested daily, during the temperature peak. It’s not a speculation; it’s there on paper: she went into the hospital without these bacterias, after the first operation she was infected with Staphylococcus aureus, and after the second with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Therefore she couldn’t be transferred to a clinic abroad. When they received the translated documents they told us that they couldn’t accept someone infected for fear of risking the health of their other patients. She had to stay in Romania.

After they performed surgery for the second time, the doctor, who was also Chief Surgeon, went on holiday to some island, and was off the scene for weeks. He left a resident with us, someone whom at one point I found screaming at my mother in her room. I called her out to the corridor and asked her what the problem was. She told me sharply that mum didn’t want to get out of bed. I asked her whether she had read her chart. I asked her, “What’s written on the chart?”.

“Cancer.”

“No-no-no. On the first page, what does it say?”

Her eyes opened wide.

“It says SLE. Do you know what SLE is? Systemic lupus erythematosus.”

Then I asked her if she knew what the life expectancy was for a patient with lupus, and told her that my mother had surpassed it by some twenty years, and hers has been a case-study in university for the past fifteen years. I asked her what that says about a patient: that she is the kind that makes every effort to live, or one that doesn’t care? Finally, I asked her what her haemoglobin level was today. I said, “It’s written on the page: Five. What is the normal level for a patient, for an average person?”

“Between ten and twelve.”

“Why would you cause such a ruckus in front of a woman with less than half of the blood she needs in her body?”

And I told her that if I caught her shouting at my mother again, I’ll throw her through the door and then through the wall.

When mum was infected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa, she needed a very powerful antibiotic called Zyvoxid which cost about €400 at that time. And we needed three boxes. The €20,000 for the bribes and all the medicine in the hospital, we had them at the time, we had savings and some private pensions that Andrew and I cashed in, and we sold mum’s car, but when we reached the limit we had to borrow. And back then raising money for three €400-boxes by the next day was a lot to ask. I knew that as a cancer patient mum had the right to drug compensation because she had been diagnosed in the terminal phase. I had her file to support the claim, but the file was rejected in the first month. I asked why, since we had all the required documents, all the stamps, all the blue-ink signatures. For three months in a row I was in front of this committee and each time the file was rejected. That is, it wasn’t exactly rejected, but neither was it approved.

We didn’t benefit anything from her legal entitlements. After having worked and paid her taxes, her social and medical insurance, there was no benefit to her from these rights at all. I went to the family doctor, because of her diagnosis the cost of this medicine was completely covered by the authorities. I went to every pharmacy around until I realised that the drug wasn’t covered by the Romanian Health Authority because it was very expensive. So then I called a cousin that was working for a pharmaceutical company that was distributing medicine to hospitals in Bucharest. I said, „Listen, help me get a hold of this medication.” She told me the hospital had this particular drug in their warehouse. „I know exactly how many vials they have, how many tablets they have. Go to -1, you’ll see the warehouse there, and tell them it’s to be administered to the patient currently in hospital under the care of the professor.” So, that’s what I did. I said, „Hello, I am the son of this professor’s patient, my mother was admitted to Surgery No. 2, and I understand there is a medication called Zyvoxid here that my mother needs.” „But how do you know that we have Zyvoxid?”, the woman replied.

I was already on the phone with my cousin. She says, „Put her on the phone.” The woman started screaming at my cousin, asking who was she to say what medication they have in stock, and then just hung up the phone, looked at me and said, „If you love your mother, put your hand in your pocket, buy the drugs and stop playing detective with us. Or else we we’ll get her out the hospital with her guts hanging out.” Those words I will never forget. That’s exactly what she said. I left the place, made three more phone calls, I managed to cobble together €1,200 in two hours and I bought the pills. I returned to the hospital. My mum was in intensive care, I found her trembling. „Please be nice” she said, “don’t get in an argument here. They told me they are discharging me.”

When her condition got visibly worse, she couldn’t even lift her hand, couldn’t even speak. She weighed thirty-seven kilos. Unable to eat, to chew; she was fed through a tube. When I had to go back to work (I was on unpaid leave without pay, and had already missed months of workdays), Andrew stayed with my mum from morning to evening – he was basically telling everyone that he was working from home, when he was actually working from the hospital ward. It was a traumatic experience for him. The Romanian system is a long way from the NHS in Great Britain. In the four months that mum stayed there, no one came to wash her. No one. The only ones doing it were us, two to three times a day. Andrew was shocked when he saw the state of the ward room, shocked when he saw that the colostomy bag was emptied into a bottle of fabric softener cut open with scissors, shocked to see that the nurses who served meals from the food-trolleys were wearing household rubber gloves – the same non-sterile gloves they used to collect towels and sheets full of pus and blood.

It was the bacterias that killed mum, not the cancer. My mother died because of septicemia. It was a giant loss for me, but also for my friends. I never felt that my mother was my best friend, but that my mother and I were the same person. She was my soulmate.

I started to understand that life can change very quickly. All my long-term plans, like working all the hours I could and saving up for when I retire to a house by the sea, became a pipe dream.

I decided to resign from my job as the marketing and communications director for a hotel belonging to an international chain. Then I packed a backpack and left. After two and a half years spent living in other countries and coming home only for weddings and birthdays of my friends, I realised it was very nice to be respected, it was very nice to have rights. That it was very nice to go to the hospital if there was something wrong with you and not to have to pay bribes, and instead to have the doctors thank you for trusting them. To have a system that works easily, and to feel respected by the authorities. To not feel that you are bothering someone by asking for information; to not have them rolling their eyes at you and waiting for you to slip them a few quid – and if you don’t – getting sent to the registry office and 243 other counters.

So I came to Madrid with Andrew. Things settled, he looked for a job at the British Embassy, got it, and moved there four months ago. In June we found an apartment, signed the contract in October, got the keys and now we’re starting renovations. During this sabbatical year, photography was one of the things that I took up again. I studied photography in college, but back then I was more interested in composition, in landscapes; definitely not in people.

NAKED was triggered by body shaming. The project wasn’t planned in the first place, but evolved along the way. The first nude photos I took were of some friends during a holiday on a beach near Alicante. It happened that two gay friends, a Romanian and a Spaniard, had joined us and I took some pictures of them for a laugh, and they told me how much they liked them.

I uploaded the project on Instagram and Facebook. People started writing to me, telling me about their experiences – it’s a project through which I’m trying to fight homophobia, racism, ageism – and it grew bigger and bigger. FAMILY was a natural next step after NAKED – my motivation was the referendum that was meant to change the definition of the word “family” in the Romanian Constitution. I wanted to show the ordinary in a relationship between two men.

The most common job amongst the 250 men I photographed? Teachers. From kindergarten educators, to highschool teachers and university professors. I wanted to show the diversity, to reveal that these people are also engineers, doctors and truck drivers. They are also the unemployed, the people who wash dishes in restaurants and the HR managers. Each one I had to portray according to his personality, according to the stories he told and the stories I saw on his body. I’ve seen scars that most people don’t see, I’ve seen surgeries, I’ve seen scars from stabbings, I’ve seen some personal things, and then I would also ask about these.

These men face the same problems faced by heterosexuals who encounter racism or body shaming. Homophobia is, of course, specific to our community. They are people who simply want to be able to live their lives, without asking permission to love who they want or to live with whom they wish. Many of of them come from countries where even I thought things were less complicated for gay or bisexual men: Netherlands, Spain, France, UK.

The first invitation to exhibit came from Brussels, the second from Paris; and then one came from Madrid to exhibit in a gallery there, and I eventually showed it at the International Gay Film Festival, LesGaiCineMad. Back home, I said to myself, „Why not show it in Bucharest?”. Although I didn’t expect it, the first exhibition was at the National Museum of Contemporary Art (MNAC) in Bucharest. It really was a surprise. I didn’t think I would get a spot there because we’re talking about another league, and because I didn’t think there would be an openness to it.

All the photos were taken using my phone, and the editing too. I chose to shoot in black and white because I wanted people to focus on the subject, not on the environment. And I wanted to have a contrast that’s very raw, in your face. I didn’t think the project would catch on that much, that I would win a prize or anything; it was something that I started from a conviction and from a need of my own, and of the community that I belong to.

Some are very surprised by the intensity of the stories – there are some frightening ones, with people who were close to being killed because of homophobia. The constant stress, the mental trauma, these surprise them. The gay people that I talk to are very excited that such a project exists and they say that it helps them.

I want to show that diversity is normality. That’s what I want to shine through: the ordinary. The ordinary of the relationship between two men. To everyone I heard on television before the referendum asking again and again: „What do I tell my kids when they see two men walking hand in hand on the street?” I wanted to show that it’s not so terrible, not so bizarre. And their inability to explain something ordinary to their kids should not restrict my own freedom.

I had people tell me: „I’m tired of seeing all these fat, hairy men; why don’t you shoot more handsome, younger ones?”. I replied, „This is exactly the point of the project, you’ve missed what it’s all about.” And if they were all fat, and if they were all old, all hairy, all with beards, I cannot control it because I don’t approach the people, they approach me. Of course I photographed men with six-packs. I’ve also photographed men aged nineteen, aged seventy-six, bearded men and men with no beard at all, fat men, skinny men, tall and short men, Chinese, Arabic, Black, men of all sorts. But I don’t choose them this way. It’s irrelevant what I like in this regard. I want to show diversity in all its forms, be that ethnicity, body type, age, and so on.

In Romania, most of the women who came to the exhibition said to me: “God, these men are more masculine than my husband. Are they all really gay?” Yes, they’re all gay.

The first thing we do when we get to Madrid, Andrew and I, is hold hands. We don’t do it ostentatiously, because it’s not ostentatious here. It’s something ordinary. No one is looking at us because we’re two men holding hands. It’s one of those countries where being gay is just as ordinary as having brown hair. That’s what I’ve wished for. For someone to look at me without thinking about how I have sex, because in Romania that’s what it’s all about: being gay is about having sex. It doesn’t matter what you’re able to do, who you are, what you have done, what kind of person you are. It only matters that you have sex with another man. That’s all.

I haven’t moved entirely yet; my house is in Bucharest now, I have things there, furniture, clothes, pictures. But the moment I move out will be very difficult. And this is what kept me tied to this place: my friends and the stubbornness that we could still change something. Romania for me was the place where I felt good. I have a home where I felt good, I was lucky enough to have extremely interesting jobs and to have been paid enough to have a decent life that allowed me to travel and do the things I wanted, with no extravagance. I have a circle of friends that I’m sure I can’t match or recreate because we’re talking about twenty and thirty-year-old friendships. When my mother died, I understood that this country is not the place where I can afford to grow old. I can’t allow myself to live on a 500-lei-per-month pension like hers, which could not even cover her meds. So why should I stay?

If up until my 44 years all my friends who’ve left the country heard me say things like: „C’mon, stay a bit longer, let’s try some more, let’s see, it’s still possible, look – just a little more patience and we can protest some more, let’s do it, let’s change things”, the moment I understood that there is no chance, for as long as I live, that things in this country can become normal, all my younger friends telling me they’re still trying to change things, all they hear from me is: „No. Don’t stay here anymore. I thought the same way when I was your age, I was idealistic, I was naive, I don’t know.”

I chose to see only the beautiful things, chose to see only my friends and the wonderful people around me, about a hundred people basically, but they are irrelevant and will always be irrelevant in a mass of people unconnected to that world. And everyone is shocked, because all my friends knew me as probably the only one in the gang who didn’t want to leave Romania. And the one who did everything he could to convince the others to stay.

It’s not easy for me to say that staying here all these years was a mistake. Had I lived in a country where everything was simple, I believe I would have developed more as a person. I would have been more creative, much more relaxed. Had I left when I was twenty-three, when I was offered my first contract and I was a kid… I think my mother would have had the same diagnosis, but if I was in another country, maybe she would have lived next to me and would have enjoyed the benefits of a different medical system, and she would have had a different life.

I think we all owe it to ourselves to live the way we want to. After fighting for 44 years – it hasn’t been a bed of roses for me, I’ve worked and volunteered and I always spoke up when things bothered me, I always took a stand against what I thought was wrong— I see nothing’s actually changed. Because those who make the law are the majority. And I no longer want to live in a country where the overwhelming majority of people has entirely different values than mine.

Acest articol apare și în:

S-ar putea să-ți mai placă:

Poziția ministrului Petrescu

Ioana Petrescu a lăsat America pentru România și a ajuns, la 33 de ani, prima femeie ministru de Finanțe a țării.

Noi aparitii editoriale

Opt scriitori debutanți, scoși în lumea despre care scriu, cu scaunul de lucru cu tot.

[#dordealba] Locul lui Lulu

Cafeneaua alternativă a Alba Iuliei face loc unei noi generații.