The Last Daughter

I looked into my family’s history and my hometown of Suceava for answers to the conversations I never had with my mother and grandmother.

Note: This is the English translation of a personal essay originally published in issue #34 of DoR magazine. You can read the Romanian version here.

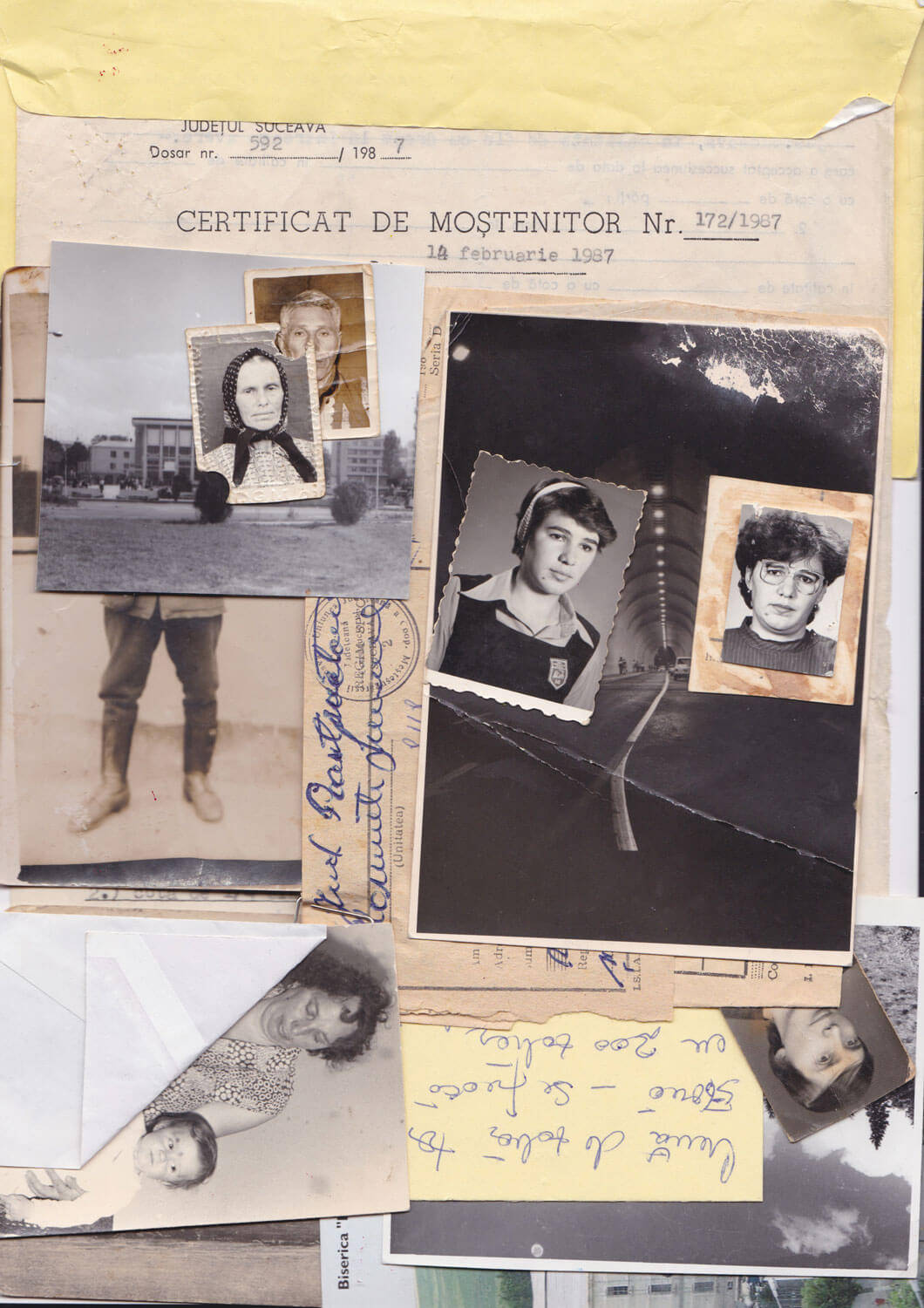

I’m the last one. The last one of my bloodline, the last one alive from my immediate family (other than a father I haven’t counted as family in 15 years), the last keeper of photos, letters and a few pages of my mother’s journal, which are hard for me to read because it seems invasive. I went alone to the notary’s office five years ago, when it was time to inherit my mother’s estate. I then squirmed and changed my mind for another two years, battling the idea of my heritage: a mortgaged studio apartment in Bucharest, a decades-spanning bank loan for that apartment, another bank loan I knew nothing about – because that was the level of communication in our family –, a burial vault at Pacea Cemetery in Suceava, our hometown.

Debt and a burial ground that contains five members of my family: my mother, my maternal grandparents, my grandfather’s parents. That’s what I get? After years of torture watching my mother and my grandparents die of cancer, that’s all I’m left with?

I rejected the inheritance. It was a way to avoid crippling debt at the age of 25 for an apartment I didn’t want to live in and that would never turn a profit. It was also a kind of fuck you to my mother. A sort of: “I won’t get stuck with these over my head because you didn’t make better decisions”.

No relationship in my life was more ambivalent than the one with my mother. I loved her, because she was my mother. A warm person with good intentions. I respected her because she had an important position in an agency handling European funds and because I learned my work ethic from her. I enjoyed her because she was fun and she listened to Snoop Dogg and 50 Cent. But it infuriated me how absent she was in the first years of my life, and all the bad decisions she made for us, including staying married to my father for 17 years. I blamed her because I had to grow up with a violent alcoholic while she was away on business. I blamed her for being blind to my suffering.

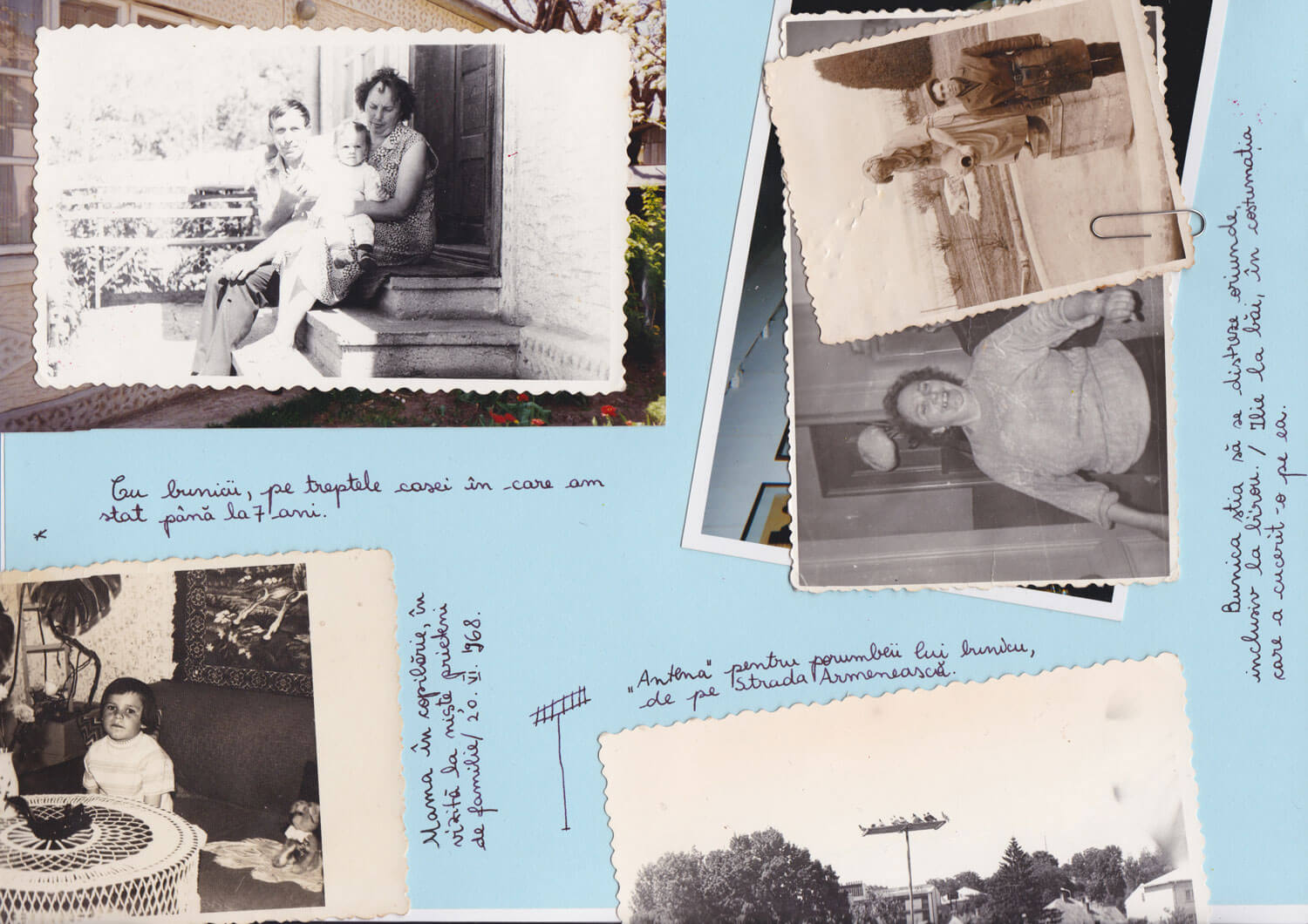

In contrast, my maternal grandparents from Suceava were saints to me. I always saw them as simple people who didn’t know how open-minded they were. They raised me as their own, I called them “mom” and “dad”. My grandmother was cheerful and talkative. My grandfather raised pigeons and tended the garden. I loved the house I grew up in, in the town centre, with big white windows, a house I promised I would never sell and I’d move in after I retired. But my mother sold it after my grandfather died, in 2010, with my approval. I wouldn’t have been able to pay for my MA in the United Kingdom otherwise. The new owners tore it down and built a mansion.

Since then, I only went to Suceava in 2013, to bury my mother. I didn’t want to see the consequences of my broken promise. I thought that seeing that plot of land without my house would destroy me, so I avoided not just a trip to Suceava, but also the people there. Out of our extended family, I only had my grandfather’s cousin, Eufrosina, whose calls I gave up answering because I knew what she wanted to ask me: when will I come to Suceava and take care of some paperwork so that I could keep the family burial vault? When will I at least visit? I didn’t want to think about it. I didn’t want to keep remembering what I had and lost. I didn’t keep in touch with Ioana, the childhood friend I had spent summer holidays in Suceava with, either. And I also didn’t keep in touch with Ioana’s mom, Rodica, one of my grandmother’s best friends.

Last fall, I went back for the first time since my mother’s funeral. I initially spent a few days there during the referendum for defining the Romanian family in the Constitution as the union between a man and a woman. I used my reporting work to build up the courage for the trip. I found a town where the familiar and the unfamiliar are entangled, and I started to think about the grandparents I lost, and what I learned from them. I thought about my mother, who grew up with her maternal grandparents, just like I did with her parents. I thought about how she blamed her mother for being too controlling, the same way I blame my mother for only being there towards the end, and then leaving for good. I thought about my house, which doesn’t exist anymore, and the weight of my memories, a weight that persists even without a physical anchor.

I felt the need to look around and, maybe, one last time back into my past, so I could understand who I was at 30 and how I got there. So, in October 2018, I visited Suceava for the second time in a month.

I went to preserve whatever was left.

I arrived in the evening, after a paralysing seven-hour bus ride and I checked into a hotel close to Armenească (transl. Armenian) Street where I grew up. My room reeked of cigarettes, and the old furniture was superficially painted white. I cracked the window and unpacked my winter clothes, batteries, recorder, camera, iPad. I also took out a grey file that had “Ioana” handwritten on it.

I told myself I’d take care of it later.

After a hot shower, I decided to watch the movie Dumbrava Minunată (transl. The Enchanted Grove), based on my favorite childhood story of a little girl called Lizuca and her dog, Patrocle. I was adamant to understand Suceava by any means, and the story’s plot is based in the county. It made me, when I was about five, want nothing more than a dog and a hollow in a tree that I could crawl into and discover a magical world. I got the dog, but I never found the hollow. The movie is bad, it’s a Communist ode to the Romanian peasant and it demonizes bourgeois city people. But it was uncomfortable how much I identified with it.

Lizuca was a “poor little girl” whose mother had died, and who was taken away from her grandparents by a shallow father remarried to a shrew. So far, all pretty similar, except for the evil stepmother: my parents uprooted me from Suceava, where I’d been living with my grandparents, when I was seven. I would have given anything to stay. I kicked and screamed so badly they had to fly me to Bucharest, because no one could’ve survived the seven-hour car ride with me. And I also became an orphan like Lizuca. It just happened later: I lost my mother at 25. By that time, my father and my maternal grandparents were gone as well.

The next day I saw aunt Eufrosina, or Fruzica as everyone calls her, in her small one-bedroom close to the Small Market, where she’s lived most of her life. She was glad to see me, although this second visit in a month surprised her. She seated me in an armchair, next to a vintage wooden bookcase that displayed framed black-and-white photos of her youth, books, porcelain statuettes and knitted table mats. She fed me pear pie that she had baked and apple juice brought from the countryside. “So what exactly do you want to do, a sort of research?” she asked me in a serious tone.

She’s 75, but won’t show it. She’s tall, like everybody in our family. Her hair was recently dyed a platinum blonde. She was wearing a peach-coloured sweater and black tights. Her only problems are the rheumatic knees – but she had just completed a round of physiotherapy and was doing better – and her teeth, which she was going to handle in a few days. I remembered that, at my mother’s funeral, some of the folks coming from Bucharest asked Fruzica how come she looked so young and wrinkle-free at her age. “I didn’t have a husband to put me in the ground,” she replied. She didn’t have any children either, or any regrets.

I don’t know if she realised, but I felt like I let her down. She’s known me my whole life, and was always around the house when I was little, but we were never close and I didn’t know how to turn a relationship that was always mediated by my mother or grandmother into one that could stand on its own.

Whether I like it or not, though, Fruzica is the closest family I have left. And I needed her to tell me about my family’s history. She showed me old pictures – of my grandmother when she was young or of my mother as a teenager. She allowed me to take her picture, but only in her new brown hat, with a narrow brim. She told me about her 90-year-old sister, Ileana, who still lives in my grandparents’ village close to Suceava and who had been close to my grandfather. We spoke about Costan too, my grandmother’s cousin, who had a habit of filming family events when I was little – I was hoping he still had the tapes somewhere. Fruzica and I even planned a trip to the village, so she could show me the house my grandfather grew up in – which I only saw twice during my childhood –, and the house where my grandmother had lived. They both looked the same as they did back in the day, Fruzica assured me. I was delighted.

I also met with Rodica Kroner, my grandmother’s friend and Ioana’s mom. She’s one of the funniest people I know, who laughs more than she talks, and sends me cat photos on WhatsApp. “I prepared a mise-en-scene,” she told me pompously when we entered Ioana’s former room, with butterflies on the walls. On one side and the other of a desk she had placed two chairs. On the desk, there were three trays: with Turkish delights, mints, peanuts and chocolate pennies.

Rodica is 72 and a mother-of-three, of which Ioana (30) is the youngest. Her son and oldest daughter are more than 10 years older than Ioana, who’s always joked that she was “the accident” because her mother had her when she was 42.

She was never treated like an accident, though. The relationship between Rodica and Ioana is one I would’ve liked to have with my mother: open, sprinkled with jokes and mockery, full of trust and freedom. When I went out with Ioana during our teenage years, Rodica was my ally in front of my grandparents. If she knew where we hung out and would commit to collecting us off the streets at night, we’d be free to do whatever we wanted.

One night, during summer break, I was at their apartment jostling with Ioana in front of the mirror, putting on make-up before heading out to a club, when my grandmother called: “They said on TV there’s a rain alert, the high floods are coming!”. We looked out the window – it was certainly raining, but there were no floods. My grandmother, however, was adamant: the “children” should stay home. Rodica saved us. She offered to walk us to the club herself, with umbrellas, to convince my grandmother that everything was under control and nothing would happen to us. “Early in the morning she called me: where are the girls?” she recounted laughing. “I told her: they’re asleep, I won’t wake them up. You guys were still at the party.”

The night of the high floods is alive in Ioana’s memory as well; we still laugh hysterically about it. She was surprised, like everyone, by my visiting Suceava twice that month. “I’m not used to seeing you this often,” she texted me when I told her I was coming back. She couldn’t understand what I wanted to write about Suceava, a town where nothing happens, especially since I hadn’t been there in years.

We came into the world two months apart. We weren’t close while growing up because our families made the mistake of comparing us. “Look, Ioana Kroner’s learning German,” my grandmother used to tell me. “Look, Ioana Burtea got accepted into a bilingual class in middle school,” Rodica would tell her. Each of us was convinced the other was a nerd, until one summer, at the end of eighth grade, when I was in Suceava for the break and our families practically forced us to hang out. “Listen, if I light a cigarette can you please not tell my mother?” Ioana asked me while we were listlessly waiting at a street crossing.

“You smoke?! Give me one!” I screamed in relief. We became inseparable throughout our adolescence and spent every summer, spring or winter holiday together in Suceava. People called us “Ioana squared”.

Then, our lives went separate ways and we talked less and less. She went to university in Iași, near Suceava. I started university in Bucharest, almost immediately got a job at a news agency and, on top of everything, I was in a relationship that consumed my every breathing moment. We kept seeing each other at funerals: at my grandmothers’, a couple of months shy of my 18th birthday, when we hid behind some tomb stones with a small bottle of vodka and a pack of cigarettes. My grandfather followed three years later. And five years ago it was my mother’s turn, when Ioana and Rodica sat on a bench close to the church with me, away from the ceremonial madness, and made me laugh a little. Ioana is now a translator, she lives with her boyfriend close to the city centre and they have a beautiful, but mean white cat named Oz. And no matter how much time goes by without contact, we’re back to our usual dynamic in less than a minute.

Even if the first few “interviews” with people from my past turned out wonderfully, things got soon got complicated. Fruzica told me her sister changed her mind and didn’t want to be interviewed or have her picture taken, because she’s old and forgetful and not in the mood.

I then relied on my grandmother’s cousin, Costan, who still lived in Liteni, my grandparents’ village. But I showed up in his life at the worst time – his wife was in the hospital, terminally ill, and my family research was the last thing on his mind. He told me he didn’t keep the family videos, but that I could go with him to the village one afternoon. Then he left me waiting in the bus stop. He never showed up and didn’t return my calls. I thought something must have happened to his wife, but it wasn’t that. I never got an explanation.

To compensate, I followed other leads. I read the local press, because each morning in Suceava used to start with my grandfather buying the newspaper Crai Nou (transl. Crescent Moon) from the nearby bus station, and sharing it with my grandmother and I. I used to get the crossword and horoscope page. It’s one of the longest-lasting rituals I remember from my childhood, more so than going to church or to the market.

I found out how the city changed in the past 10 years. It’s home to the least safe neighbourhood in the country, Ițcani, where there’s no police station and little street lighting at night. The city is overall the second most dangerous in the country, surpassed only by Alexandria in the south. Ioana was mugged last year in front of her building by five masked men, in an area of the city centre with no street lighting, across the street from the county court. She didn’t even think about reporting the incident, because she knew nothing would happen.

When I tried watching the local TV station, Bucovina TV, I stumbled upon the ridiculous. I saw a commercial for vanilla essence with a popular folklore singer, Daniela Condurache, dressed in a traditional outfit while baking Moldovan cheese pies. One of the news stories meant to bring peace into the souls of the viewers was that the national Folklore Music Award would be staying in Suceava for another year. They also featured a few cute moments from a local high school’s junior prom. They had choreographies on Kangoo Jumps boots, folklore dances and modern reinterpretations of Romeo and Juliet. At the end of the news forecast, the anchor reminded viewers Saint Dumitru was around the corner, “the last and very important autumn celebration”.

To get a full picture of the town, I went to the library and the museum, and searched for the 89-year-old photographer who’s been documenting Suceava since he was a teenager. Dimitrie Balint collected a treasure of hundreds of photos, but he was also hard to track down and kept postponing me.

I even went to see Romanian president Klaus Iohannis’ surprise visit to the local medieval castle. He was well received in a county where, since 2004, the mayor is from his own party. Ensembles of traditional dancers and singers gathered at the castle to serenade the president. The town leaders were all there. But the local media barely reported about the event, so there were only about 30 people waiting in the parking lot to see Iohannis. People were disappointed he didn’t talk to them and only waved from his car, like a prince that doesn’t mingle with peasants. That’s how folks from Suceava feel about local leaders too. Rodica told me the story of the local administration is one of “indifference and incompetence”. That’s why the roads are filled with craters, there’s chaotic construction all over town, and some streets aren’t lit at night. “It’s been a long time since we’ve had any Bratianus,” Rodica said, mentioning one of the most influential families on the Romanian political scene of the early 20th century.

On top of that, Suceava was the county with the highest ballot turnout at the referendum for redefining the traditional family, that I covered a few weeks earlier. It didn’t sit well with me that a quiet, ethnically and religiously diverse town like Suceava became a victim of post-communist transition and of the messages promoted by the Coalition for Family, a nation-wide conservative organisation that stands against gay marriage and women’s reproductive rights. In a local newspaper, I found an op-ed written by the spokesman of the Moldova and Bucovina Metropolitan Church complaining that priests are being discriminated, that “priest hunters” are after them and they’re subjected to media lynching. I wondered how it must have felt for a gay teenager in Suceava to read that priests feel like they’re “the most blamed social category in Romania”. Especially in a county that doesn’t welcome drivers with the sign “Welcome to Suceava”, but with one reading “Welcome to the Land of Monasteries”. I asked Ioana if she’s ever heard about someone being gay in Suceava, and she replied with a stare and a groan. “What’s wrong with you? They’d beat them on the street. If someone was gay, I doubt they’d stay in Suceava.”

I quickly became absorbed with documenting the town, but I’d forgotten it was more important to document myself.

On the fifth morning, I couldn’t get out of bed. I’d caught a bad cold and a high fever that was giving me the chills. Time was running out and I didn’t feel like I was doing enough or getting anywhere. I had roamed the streets with a camera dangling from my neck in search of the town’s essence and all I’d gotten was a cold. That’s why I came all that way?

I started weeping still tucked in bed. “I feel like I have no idea what I’m doing,” I wrote to a friend of mine. I told her I felt sick and guilty that my grand investigation wasn’t going well enough after the magazine had spent a lot of money on it, and that I didn’t have time for a break. “Fuck your guilt,” she replied. “This is your fucking story. You do it on your own terms.”

To make myself stop crying, I threw on some winter clothes and went into the city. I walked aimlessly towards the city centre, the bus station, then Armenească Street. I stopped in front of my old house, which had become a villa with several additions and little towers in beige and brown. I had been there with Ioana during my first visit in October, when our reactions were limited to “oh, wow” and “holy…”. It’s beautiful, we agreed. My old neighbours’ house, behind which ours was tucked, is another story though. It’s now a bunch of old wooden plaques reclining on rotten walls, surrounded by a blue net that’s meant to keep it from falling on curious visitors. Half of that building used to be the home of Bicu and Bica Costea, an elderly couple who looked after me while my grandparents were still working. The other half belonged to a German family, the Săveanus. The building was called Hopmeier House and it had been there for about 130 years, one of the oldest standing houses in Suceava. Formerly standing. City Hall left it to rot. I started crying again, with clenched fists. I wanted to sit down, if only for a second, but I didn’t have any place to do that.

I walked towards my old kindergarten, a few houses up the street. There was no sign of people anywhere in the neighbourhood. I found the old building painted a hysterical pink, but other than that it was just as I remembered it: a big, tin-roofed house, with an upstairs and small windows, and a small backyard with a few swings. In that house, I played Little Red Riding Hood for the annual play, when I was about three or four, and I forgot all my lines on stage. I started playing with my red apron to distract people and everybody started laughing. My grandmother, who was sitting in the front row, helped me through every single line, reciting loudly for me to hear her, and I followed her lead to the very end.

I crashed on the sidewalk in front of the kindergarten, hidden behind a parked car, and continued weeping. I wandered back towards my house, but felt like I was going in circles, because I had nowhere to stop and nowhere to go. The street seemed shorter in length. In front of the Lutheran church, a black cat blocked my path and started meowing and swirling through my legs. I sat on the sidewalk again, crying with the cat next to me.

I had come to Suceava to learn about my family, to understand our history, but I lied to myself thinking I could do it as a journalist, that the usual rules would apply to this process. My perfectionism and the fact that I have no idea how to handle my emotions without panicking almost destroyed the experience for me. I have no patience for myself. That’s probably the main issue: I don’t allow myself weakness, everything needs to be carefully planned and correctly executed.

That’s also a family inheritance.

My grandparents were peasants. They were born in a village called Liteni, in the Moara township, 12 kilometres from Suceava – my grandfather in 1933, and my grandmother, eight years later. Before the First World War, the village had been the border between Bucovina (then a province of the Austro-Hungarian Empire) and the Kingdom of Romania. My grandmother, Malina, told me she had four other brothers and sisters, but they all died during childhood. My grandfather, Ilie, lost a sister when she was 14 and two brothers when they were even younger. My grandparents became only children – the survivors.

Despite hardships, their childhood and adolescence seem to have been happy, at least according to what they’ve shared with me and what aunt Fruzica recalls. My grandfather was one of the eligible bachelors in the village, always elegant and ready to join the hora. “He was a real pedant and he liked to dress nicely, even though he was living in the countryside and the clothes were traditional,” she said. For religious celebrations, he needed to have a new shirt, new hat, new shoes and a handmade bedazzled girdle as men wore back then. His parents were rich peasants. They owned seven hectares of land and were able to buy a big house with a garden in Suceava – the house I grew up in.

My grandfather worked on the family land day in, day out. There was nothing else he’d rather have done. He loved the countryside and always presented himself as “a farmer”. The city wasn’t his cup of tea. What saved him in Suceava were the garden and the pigeons he nurtured and trained for races. Fruzica told me that, when life became a bit too hard, either at the storage facility of the transport enterprise he carried auto parts for, or when he missed his village, my grandfather used to play a song on the harmonica: “Why did you send me away from you/ Why did you send me away from home? / If only I’d be a young ploughman / If only I’d stayed near my scythe”.

My grandmother was quicksilver. “People noticed her even as a little girl,” Fruzica, who was two years her junior and went to the same school – the only school – in the village, told me. She wasn’t a dazzling beauty, but there was something about her. “Do you know how some people can have a beautiful face, but they’re not attractive at all? She had a certain kind of beauty in her personality. She knew how to talk to people, how to attract them.” She was the best in school and the best at local dances. You had to live under a rock to not know about Malina Pascari in 1950s Liteni. She married a young man from the village when she was 16. Fruzica remembers it was almost winter when the ceremony took place and all the children in Liteni piled up to see the bride. She wore a long, white dress, with a macramé veil that touched the ground. The veil was swollen at the top of her head, as she wore a small crown underneath it, according to tradition in those days. “I remember she was at the fountain near her house. She was surrounded by youngsters, the best men (vătășei) and the maids of honour (druște). She was in a great mood.” My grandfather might have seen her on that day too.

He wasn’t married although he was already 24 and slowly entering “hopeless bachelor” territory. It wasn’t that girls didn’t like him. It was that his mother’s standards were impossible for any of them to meet. At a certain point, girls began avoiding him.

Malina’s married life wasn’t going any better. She got a divorce a year after the wedding, but the reason is still a mystery. Fruzica claims she doesn’t know why things didn’t work out. Rodica says my grandmother told her the guy wasn’t malleable or willing to allow her powerful personality to take centre stage. My grandmother told me her first husband was a violent drunk, but nothing more. What’s clear is that she didn’t stay single for long, because four years later someone was desperately looking for a wife.

“Ilie was almost 30 and wanted to get married,” Fruzica recalls. He asked two of his cousins for advice, and one of them said his only candidate should be Malina, because she was hardworking. That was that.

I always wondered how they accepted each other, with all the baggage they had: him, a lost cause for marriage, with a mother that scared away all potential girlfriends; she, a divorcee with no inheritance, little education, and a bit too big a personality for those times. Maybe it was precisely that they both had baggage. Maybe they needed each other to reach a respectable social status. They didn’t bother with a religious ceremony or other formalities. They just signed the papers at the mayor’s office and immediately moved to the city. Ilie had found a woman who wanted to lead, who would let him be with his farming and his pigeons. Malina had found a quiet man who, in his black leather overcoat, black fedora hat and dark sunglasses, looked a bit like Alain Delon, her favourite actor.

A year later, in 1963, my mother, Victoria, was born. People in Suceava called her Ritza, a diminutive, and later in Bucharest her colleagues and friends would call her Vicky. I often heard about how happy my mother was growing up in the countryside, with her maternal grandparents and other relatives, but we never went any further with those stories.

After her death, I found the grey file that had “Ioana” written on it, on her paperwork shelf. It was her handwriting. I opened it with my heart in my throat and saw she had collected the family recipes for me: the plum dumplings, cheese pies, the Easter cake that was creamier than any bakery cakes, and so on. Underneath those were six yellow pages from my mother’s diary. I recognised them because I knew the notebook she was writing in, after she’d been diagnosed with cancer. I read the first line – “Why am I writing this?” – and closed the file. It stayed closed for five years, because I didn’t have the courage to read those pages, just like I didn’t have the courage to go to Suceava. I thought maybe it’s about her marriage, maybe it’s about the disease, maybe it’s about me.

I read them in Suceava, though, after I finished crying in the neighbourhood I’d once lived in. For days I’d been moving the file from my backpack to the closet, from the closet to the table, from the table to the chair. It caused me anxiety, but I knew I had no business seeking any spiritual inheritance in Suceava if I wasn’t capable of looking at the inheritance my mother wanted me to have. The diary pages turned out to be about her childhood in Liteni. And I’ll let her tell this part of the story, because it doesn’t belong to me.

“What should I begin with? My childhood, obviously. I’m already smiling, because it was the best time of my life and I’m not using big words.

I was born in the village of Liteni, in the Moara township, county of Suceava, on 10/10/1963. In the beginning, everyone said it was a lucky sign that my day and month of birth matched. In the beginning, I believed the same, even though things didn’t turn out that way. As for the place itself, Bucovina is second to none. In those times, Liteni was a township and, from what I could find out, I was born at the hospital in Zaharești, a nearby village. I’m going to say a few words about my ancestry, following my maternal grandparents’ origins. My mother’s maiden name was Pascari and her first name was Malina – a beautiful, common name in our family. An aunt and one of my mothers’ cousins were named the same. Her parents, George and mama Paraschiva, whose name I inherited as well. And they also named me Victoria after my godmother Tolița, one of my grandmothers’ sisters.

I remember my grandmother as an extremely kind woman, very smart. She was a team leader at the local cooperative [during Communism], so she was practically a manager, a leader and I think I inherited some of her qualities, including that of leadership. She was a beautiful woman who married when she was 13. Her maiden name was Haveliuc, her mother was Rozalia and I never met my great grandfather. They lived at the edge of Liteni bordering Frumoasa village, in a place called bahna because it was swampy. My great grandmother died when I was a child, I can’t remember exactly when, I don’t think I was in school yet. But I remember she was a very old woman whom my grandmother cooked for and every time we visited she would start telling stories from her youth, and every time she would tell the same stories. From what I gathered, they were very poor, didn’t own a lot of land, had a difficult life and many children.

We were closest to my uncle Ion’s family, because they lived on the same street as my grandparents and because they knew how to create a welcoming atmosphere. Even though they had a lot of children, they always laid every bit of food they had on the table for us. Profira was a cheerful, quick witted woman. My uncle Ion was kind of grumpy, he worked long hours at the cooperative taking care of the horses. But it was a pleasure to be in their home, even though I remember that at one point they all lived in one improvised room in their shed. Later, they built a small separate house with a foyer, two bedrooms and a storage room. Despite everything, their home was always full, and I loved eating with them. Even today I think I’ve never tasted better eggs with sausages, or a better polenta sliced with cotton thread, in my whole life.”

There are a few other paragraphs about the history of the village, but the ones about the people my mother grew up with and what they meant to her seem essential to me. I didn’t know anything about it. I realized how similar our childhoods had been. She was brought up by the grandparents she loved until she was eight, the grandparents she believed she inherited in character. I was raised by her parents, towards whom I had the same feelings. My mother was a lot like her father, the earth-loving Ilie, both in character and physically. They were both long and brunette, calm and romantic. So different from my grandmother. I know, from stories I’ve heard and scenes I witnessed, that my mother’s relationship with my grandmother was at least as complicated as my relationship with my mother. Ever since she came into the world, my mother was Malina’s greatest project.

“She idolized your mother,” Rodica told me. “Maybe because she was an only child, and your grandmother didn’t have an easy life in the village, her family wasn’t rich folk. She cut her own path and only she knew how much she’d worked for it. For your grandmother there was no such thing as «I can’t». If you kicked her out the door, she’d come back through the window. That’s probably why her attitude towards your mother was scholastic.”

My mother was the child any parent would want. Book smart, obedient, beautiful, home early. But, for my grandmother, she could always be better. And with every bit of criticism, my mother closed herself off and detached from situations, just like she did later in her troubled marriage. Just like I do nowadays when I want to avoid something painful.

She told me about the pressure my grandmother placed on her shoulders to be a good student, go to university, get married immediately after graduation. She had to be “somebody”. My grandmother didn’t hit or verbally abuse her. But she had a way of inspiring fear in others, a way she pronounced “Ioana!” or “Victoria!” when we would upset her, accompanied by a terrible frown, that made you want to hide. Next came the reproaches that cut through our flesh: “When I think of all I sacrificed for you…”, “Aren’t you ashamed…”, “I work all day, old and ill…”. If she also started crying of rage, it was like the end of the world.

When that happened, my grandfather would go to the countryside for two days. I learned very early in my childhood to hide in the garden, behind the beanstalks. I don’t know how my mother coped, I don’t know if she developed a survival instinct fast enough. What I do know is that, no matter how bad the fight was, my grandfather and I ended every quarrel with my grandmother in laughter. She was quick in anger and quick in calming down.

My mother, however, still feared her even when she was 40 years old. While she led a department in an agency handling European funds and had to travel often, she never told my grandmother she was leaving until she was in the airport, past check-in and security. “There’s nothing she can do at that point,” my mother used to tell me. It seemed tragically funny and completely immature, but I knew she heard a lot of criticism about how much she travels, how long she’s away from her child. I understood both women.

The two most unfair events in my mother’s youth were a fight she had with her parents at the end of high school, and her marriage to my father. The former enraged her so much that she kept telling that story throughout her life. She wanted to go to her senior prom, she had been looking forward to it. My grandparents allowed her to go, but with a strict curfew. My mother had the time of her life, laughed with her friends, danced all evening and forgot to check the time. She got home half an hour late, and saw my grandfather waiting for her in the street, in front of the house. As she got close enough to him, he slapped her. Hard. It was the first and only time my grandfather hit my mother, but that slap stayed with her. “I hadn’t been drinking or smoking, I wasn’t God knows where with some boy,” my mother told me. “I was just a little late.”

The second injustice has to do with my grandmother. In college, my mother was seeing a Theology student and got really attached to him. She told me she would’ve liked to marry him, but my grandmother said no. First of all, she wanted my mother to graduate from university. Second of all: “You want to become the wife of a priest?” my grandmother asked her daughter in disdain. She had other plans for my mother.

“She didn’t want Victoria to end up like her,” Rodica told me. For the most part, her project had succeeded. “She was good in school, she did well at university, she got a good job. Your grandmother was incredibly proud. Through your mother, she probably fulfilled her own ideals.”

I don’t know what my grandmother was thinking, but I can imagine that for someone who endured poverty, who fought for every step forward, moving up the social ladder became a family project. All that was missing was for my mother to have a family of her own, the perfect family.

In order to achieve that, my grandmother consulted an old woman from her village who was a housekeeper for a wealthy family from Suceava. They had just moved to Bucharest with their 25-year-old son, a university graduate. They arranged a blind date, the young man liked my mother, and my grandmother started pushing for marriage. My mother told me she wasn’t sure about it, but Malina told her she’d better not become an old maiden, that when she was her age she was married and had a child, and that she wouldn’t find a better catch. In the end, my mother obeyed. There were two wedding parties – one in Suceava, one in Bucharest. There’s a picture from the civil ceremony, where my mother and her mother are facing each other, crying and holding hands. I always thought that was such a sad picture. Neither of them looks happy. About 17 years later, after the divorce, my mother threw away or burned all the pictures of my father and their wedding.

“The divorce really hurt your grandmother,” Rodica recalled, “because the crystal globe that was your mother, her super-idol who did everything Malina would’ve wanted to do, cracked”. She opposed the divorce as much as she could, she tried to mend their relationship. She criticized my mother for not paying enough attention to her husband and defended my father even as he drank 20 cans of beer a day, every day. She was afraid of my mother making a wrong move. But after years and years of tensions, scandals, drunken quarrels, violence and cheating on my father’s part, the marriage ended and he was out of our lives, because I chose so.

That’s when my mother was finally free from her mother. Away from Suceava, in a job she loved, she began discovering herself. “I was shocked,” Rodica, who always kept in touch with her over the phone, said. “I realized that, going out into the world, she regained her spirit… which is, in fact, your grandmother’s spirit. They were actually the same.”

My mother started going to parties, to the theatre, to restaurants. She had a group of friends and colleagues that she would mobilize for going out. She listened to their problems, just like my grandmother would listen to her friends who were seeking advice. She discovered she liked rap music, and cooking was easier if she sang The Pussycat Dolls and made her daughter cringe by starting to dance with her. My grandmother would make me cringe the same way, when all of a sudden she’d want to dance to traditional folk songs. “She got her true self back,” Rodica believes, “but in Suceava she wasn’t able to manifest that.”

My grandmother always said she got a second chance with me. A second chance at parenting and getting it right. She remained a mystery to me and is a big part of the reason I felt the need to go back to Suceava.

There are details in her past I find fascinating – her first marriage, the courage to get a divorce as a teenager –, especially for someone who did those things in the 50s. Then, her career rise. She started out as a cleaning lady at the state enterprise that traded metal and chemical products in Suceava. Soon enough, with no agenda or well-placed friends, she was promoted to assistant of the general manager and kept that job for 28 years, during which she got to meet everyone who was anyone in the region. She had a loyal husband and a house in the city centre. It was a huge accomplishment for someone in her village. She moved not one, but dozens of steps up the social ladder.

“She had a native intelligence and could learn anything,” Rodica, who worked with her at the enterprise, told me. My grandmother wanted more in life, she was ambitious. Her greatest regret was that she didn’t have the chance to stay in school and become a lawyer. She placed all her hopes in my mother, but she slowly learned from the mistakes she made.

She told me I could be anything I wanted, as long as I worked hard and became someone worthy of respect. She treated me as an equal, allowed me to go to parties even if she was afraid of high floods, told me it was important to have fun. When I spent the summers in Suceava and I had homework to do, she would pull a table in the courtyard and tell me to write there, in the sun, not locked inside the house. I got to experience her best self, the version so many people fell in love with. I grew up on a street where Jews, Armenians, Germans and Orthodox Romanians lived in harmony, and my grandmother was friendly with all of them. Our house was always full of friends, relatives and neighbours who came for a piece of advice, a coffee cup reading or simply sharing stories.

The first time she was diagnosed with breast cancer she was 50. I was little, I can’t remember, but I do recall a period of time when my parents took me to Bucharest to live with them for a few months. My grandmother had surgery, a partial mastectomy, but life went back to normal relatively fast. “She was really optimistic. She never thought she was going to die, she always said she’d get better,” Rodica said. For some time, she really was better. The cancer came back 10 years later, and my grandmother fought it another four. “When the results from her last tests came back, that’s when she said «Rodica, I don’t think I’ll make it this time»”. Her only regret at that stage was that my mother and I didn’t have a home of our own and were renting an apartment, because my father got the house after the divorce. But the separation itself didn’t bother her anymore. “How long could my Victoria put up with him?” she told Rodica.

I don’t know if my mother and grandmother ever had closure or reconciliation, although they were never officially fighting. I know my mother suffered terribly when my grandmother died, as did I. And she always said nice things about her, but constantly added: “I don’t want to control you like my mother controlled me”. Control, however, wasn’t the problem with us. It was absence.

I moved to Bucharest with my parents when I was seven, and I felt like I was living with two strangers. One of them was kind and calm, always busy with work. The other, furious and vitiated. It was hard for me to call them “mom” and “dad”, which always hurt their feelings. The best I could do was “mama Ritza” and “tata Sorin”. I liked my mother because I had heard she had a good job and was respected by many people. I would often tell my grandmother that my mom was „a lady”. But it was hard to feel close to her, especially since she left me alone with my father for so long and I cashed in all of his rage.

When I was in first grade, I began complaining about sharp chest pains and dizziness. Sometimes I felt like my heart stopped and then, all of a sudden, it would start beating violently, like it wanted to run away from my body. My parents took me to a cardiologist and pumped me with beta-blockers for arrhythmia – a common diagnosis for children who grow tall very quickly, like I did until I stopped at six feet, and that doesn’t usually require treatment. My grandmother didn’t approve of the pills. “The child isn’t sick. The child is afraid of her father,” she told my parents. I felt like my grandmother saw me, understood me, while my mother didn’t know what to do with me. And, yes, my grandmother cared about my father, but she always tried to guide him, to save him from himself. She didn’t act like he wasn’t flawed, but she made a mistake thinking he could change.

Later, after the divorce, my mother and I renegotiated our relationship as best as we could. At 16, I had piled up enough anger and resentment to fuel a whole army of black-nailed teenagers. I didn’t want to hear about any attempt at parenting, any attempt at suddenly becoming the involved parent she’d never been. By that time, it seemed like the adults in my life were the ones who needed to get their shit together and untangle their brains. My mother never understood why I was being so aggressive with her. “Hey, what happened in that house when I wasn’t there?” she would ask me.

That was the problem – that she needed to ask.

That she didn’t notice and get a divorce sooner, because she was afraid of her mother. That, as long as it wasn’t bad enough for her, as long as she didn’t know my father was a cheater, she saw no reason to leave.

When she got sick, I was in my senior year of high school and things had to change. I realised there was no more time for eye rolling and sarcastic clapbacks. And she realised that, if she wanted to be there for me, she had to adapt. I think the disease gave her, in a weird way, a new perspective. We started spending more time together and arguing less. I saw she was trying and that made all the difference. The best advice I ever got in my life actually came from her. I wanted to be more open, so I would share my romantic problems with her and ask her advice. She refused to answer.

“Don’t ask for my advice because, first of all, I’m no good at that, and second of all, I don’t want you to blame me if things don’t work out,” she used to say. “I listened to my mother and I ended up blaming her. So do what you want and take responsibility for it.”

Staying away from Suceava makes me feel guilty. People may believe I forgot my life there, but I don’t visit because I keep hoping to forget, even though I never manage to. I keep hoping it’ll hurt less, and I’ll stop missing a family that I have no way of understanding completely, a family that caused me both suffering and joy – I don’t know if in equal quantities. I don’t want to keep going back to a place where my family is gone, and walk the streets aimlessly in search of a feeling, a memory, a pattern on the sidewalk.

The day before I left, I took a walk with someone whose baggage is bigger than mine. Dimitrie Balint created a treasure of hundreds of photos from Suceava’s past, many taken by him, others by older photographers and archivists. He’s a sort of local celebrity who, at age 89, frequently goes on TV and organises exhibits. I visited the old Armenian neighbourhood with him, where he told me what he remembered about every single house. “This little house here belonged to Alaci, a professor at Stephen the Great High School,” he said as we stopped in front of a reconditioned house that looked like it used to belong to nobility, with a wooden roof and big porch, a large courtyard with apple trees and a dog that barked hysterically. An old woman with a shawl covering her head was gathering the fallen leafs. “Come here, you, Maria!” Balint yelled at the fence. “Is this professor Alaci’s house?” It wasn’t, the short woman replied, it belonged to his aunts. After so much time, Balint sometimes mistakes the houses, but he’ll ask and get the right information. And everyone knows him. “We’re looking for a family that used to live down the road, Șuleap,” he told the woman. “Șuleap?” she thought for a bit. “I think they died. Why, are you looking to buy?” she asked him. Then she insisted that her boss, a doctor who lived in the house we were looking at, should know more and invited us inside. We politely declined, we didn’t want to bother anyone.

“Who’s this?” she whispered looking in my direction. “Șuleap’s granddaughter,” he replied. The street forgot. I followed Balint as he barged into several courtyards, asking people if they remembered my family and our old house on 11 Armeneasca Street. No one did.

We kept walking on the parallel street, Dragoș Vodă, because he wanted to show me some beautiful old houses. We stopped in front of one and a boy about the age of 10, carrying a backpack, came toward us.

“Are you taking a picture of this house?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said. “It’s beautiful.”

He looked at me all confused. “Is that a reason to take a picture?”

He then asked us, walking in reverse, if we’re new to the neighbourhood. I didn’t know how to explain why we were there, so I said “yes”. He opened his arms wide, yelled “Welcome!”, and walked away.

The walk I took with Balint was, in the end, not only about what was lost: the memories of my family, the memory of the old houses on the street. The photographer gave me dozens of photos of Suceava and its people, and said he’ll leave the rest to a local priest who hosts his studio in the chapel of a church. He was disappointed by the local museum, where he wanted to donate his archive, because they kept postponing and confusing him with paperwork. He doesn’t care about that. So I came back from Suceava not just with the physical inheritance I never got, but with the history of a whole town.

On my last day there, I went to the History Museum of Bucovina, to check the official history of the town off my list. I was supposed to meet my aunt Fruzica and Ioana later, to say goodbye. The museum changed a lot, in a good way. When I was little, the only attraction was the Throne Room of Stephen the Great, the former ruler of the Moldovans – a spacious room with some mannequins dressed like in the Middle Ages, dispersed around a throne where the former prince supposedly sat. Today, the renovated museum actually looks like a historical institution. Dozens of rooms are linked to one another and tell the story of the whole region, from prehistoric times to the 1989 Revolution. I took so many pictures, my phone almost died. Before it did, I received a surprising phone call: my uncle Costan, who had left me waiting in the bus stop. I thought he was calling to explain what happened, but no. Some long lost relative of my grandmother’s found out I was in Suceava and needed a signature from me to settle a conflict about a piece of land that once belonged to my great grandmother – or something of the sort. He said he gave her my phone number so that we could reach an agreement. I didn’t know what he was talking about, but I was furious and I felt used. When I left the museum, I didn’t know where to go and I didn’t have a charger with me, so I walked around in the park near the county court for a bit, then towards the city centre, thinking I’d go to my hotel and call Ioana and Fruzica from there. Clearly they’d be upset if we didn’t see each other before I left town, and the thought unnerved me even more.

As I walked past the Catholic Church, it was getting dark. Inside, the lights were on and I could hear the organ. A blond boy with glasses was running towards the entrance. It was time for mass.

I went in out of reflex, because I remember my grandmother liked going there sometimes, even though she was Orthodox. I sat on one of the wooden benches in the back. There were about 30 other people there, and a big screen on the left of the altar showed the words to the prayers.

“We have amongst ourselves all of our dead as well,” the priest said. He was followed by 30 seconds of silence, during which every sigh toured the walls of the church. My grandmother was right. It was quiet there. Through the simple, square windows, empty tree branches looked like coal trails on the dark blue sky. “Through his painful ardour…” the priest began. “Have mercy upon us and the whole world,” the faithful responded. They repeated that like a mantra about 10 times.

I told myself I’d only stay for a few minutes, but I was there for more than an hour. I started writing my thoughts in a notebook, all the anger I felt because of my relatives, the expectations they had of me, even if we barely knew each other. In the calmness of mass and the organ’s music, it was as if my fury was crashing into the walls of that church. I always felt a tension between wanting to stay close to my living relatives, wanting to have a family in general, and all that comes with an imperfect family: the pressure, the injustice, the wounds, the resentment.

I’m the last one. I’m the last one in a long line of women who led families, raised children and went into offices their mothers couldn’t even dream of. The days I spent in Suceava turned out to be about them.

On my mother’s side, they were hardworking, intelligent women with short, intense lives. (My great grandmother died when she was 56, my grandmother at 64 and my mother at 50, all because of cancer.) They pushed each other to be better, to have more, to be happy, but they were all wrong. My grandmother had a remarkable intelligence and cheerfulness, a strong personality and fierce independence. She mobilised people and made things happen. But she never thought that was enough, she never realised that’s what made her special, not the number of diplomas she could’ve had, not that she was a divorcee at 17. She didn’t trust my mother to choose her own path, like she had done. She judged no one, except her own daughter.

My mother wanted to break away from that inheritance, but she ended up not knowing her own child until late in life. When I was a teenager, she tried to bring me close by giving me freedom to do what I wanted, but I didn’t feel like that was something she could “give” me – I had taken it without her consent anyway. I felt like she was constantly falling behind in figuring out how to approach me. I compared her to my grandmother and, not realising how complicated their relationship was, I defended my grandmother. Because we were more alike, because she usually won fights, because she seemed strong and rational. I ended up imitating her, which my mother never wanted to do. And that made me my grandmother’s child more than my mother’s, just like my mother was her grandmother’s child.

As I left the church, I was more aware than ever of the complicated inheritance those women left me. I didn’t know what I was looking for in Suceava when I came back, but I think I understand what I found. I have perfectionism running through my veins, as well as the contradiction between controlling and obeying, an obsession with making everything a competition and comparing myself to others, a need to always seem strong. I’m trying to reject that part of the inheritance, just like I did with my mother’s estate. It won’t be as easy as signing a piece of paper, but I’m doing my best.

Acest articol apare și în:

S-ar putea să-ți mai placă:

Ascultă poveștile din DoR #39 în varianta audio

Dacă preferi poveștile în format audio sau ți-e greu să găsești timp de citit, acest playlist e pentru tine. Ascultă poveștile din DoR #39 citite chiar de autori.

Lento, pero avanzo

De la paralizia alibiurilor, la libertatea de a fi responsabil.

Adina Pintilie: Dragă mamă

Regizoarea filmului „Touch Me Not” îi scrie mamei ei despre sexualitate, intimitate și alte lucruri nespuse.